The day the music died

The death of an institution

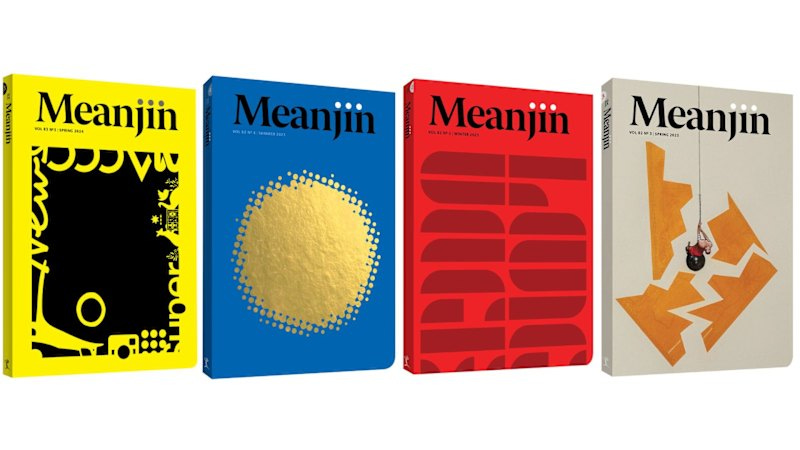

When is it that we realise that we’ve been robbed? If the house has been kept in place, and the robbery was done swiftly, when do we realise what has been stolen? This is what I’ve been wondering since the news that Meanjin, one of Australia’s longest running literary journals at the ripe old age of 85, will publish its last at the end of this year.

Hard…